When two unexpected silver scepters surface in the storage rooms of Kulturen – the region’s cultural history and heritage museum – they set archivist Henrik Ullstad off on a historical detective journey. His search for answers reaches deep into the University’s ceremonial traditions and uncovers findings that challenge the long-held understanding of these iconic objects.

Christmas is approaching, even for us archivists at the Records Management Division. Yuletide peace is settling over the Archives Centre South, and from some peoples’ speakers flows the well-known Swedish Christmas song by Lund University alumnus Viktor Rydberg, proclaiming that the star “does not lead away, but home.” This is a story about stars – and how they, at least in archival contexts, can lead us if not home, then at least on a journey “down the rabbit hole” with rather astonishing results.

On 18 December 2024 – just under a year ago – an intriguing Christmas gift landed in my inbox. The University’s Chief of Protocol had a question regarding the two silver scepters carried before the Vice-Chancellor in the University’s processions. It turned out that there were two identical scepters in Kulturen’s silver collection, and the question on everyone’s mind was what this could mean. Did the University have four scepters instead of two? Were they copies? And if so, which were the originals? And whose were the ones at Kulturen?

Let’s start from the beginning

But let’s start from the beginning. In the winter of 1667, a somewhat battered gentleman arrived in Lund – then not yet a university town – with an equally battered shipment. His name was Nils Beckman, recently appointed professor of Roman law at the planned university, and the shipment contained everything needed to inaugurate such an institution in Sweden’s Age of Greatness: robes of velvet and silk for the Vice-Chancellor and the professors, a collection of hats for the same persons, beadles’ coats, academic guards’ uniforms, University and faculty seals, and – of course – “2 pcs: Scepters of Silver, Ornamentally Gilded.” They were crafted by the royal goldsmith Michel Pohl, each crowned with a star bearing the inscriptions “Sapientia divina” (“Divine Wisdom”) and “Sapientia humana” (“Human Wisdom”) respectively and weighed 112 lod (just under 1.5 kilos). And why battered? It so happened that the professor and parts of the cargo had been “[thrown] off a bridge outside Norrköping” on the way down, damaging a few hats and injuring the professor’s arm.

The scepters, however, seem to have survived this mishap and could participate in the University’s inauguration on 28 January 1668. The inauguration was a grand five-day affair, attended not only by the future academy’s professors and staff but also by the Governor-General of Scania, representatives of the officer corps, clergy, burghers and government officials. During the inaugural procession, the “insignia academiæ” (perhaps including the scepters?) were carried on “blue cushions […] by six distinguished noblemen.” The ceremony was followed by banquets and fireworks, all befitting a university inauguration in Sweden’s Age of Greatness.

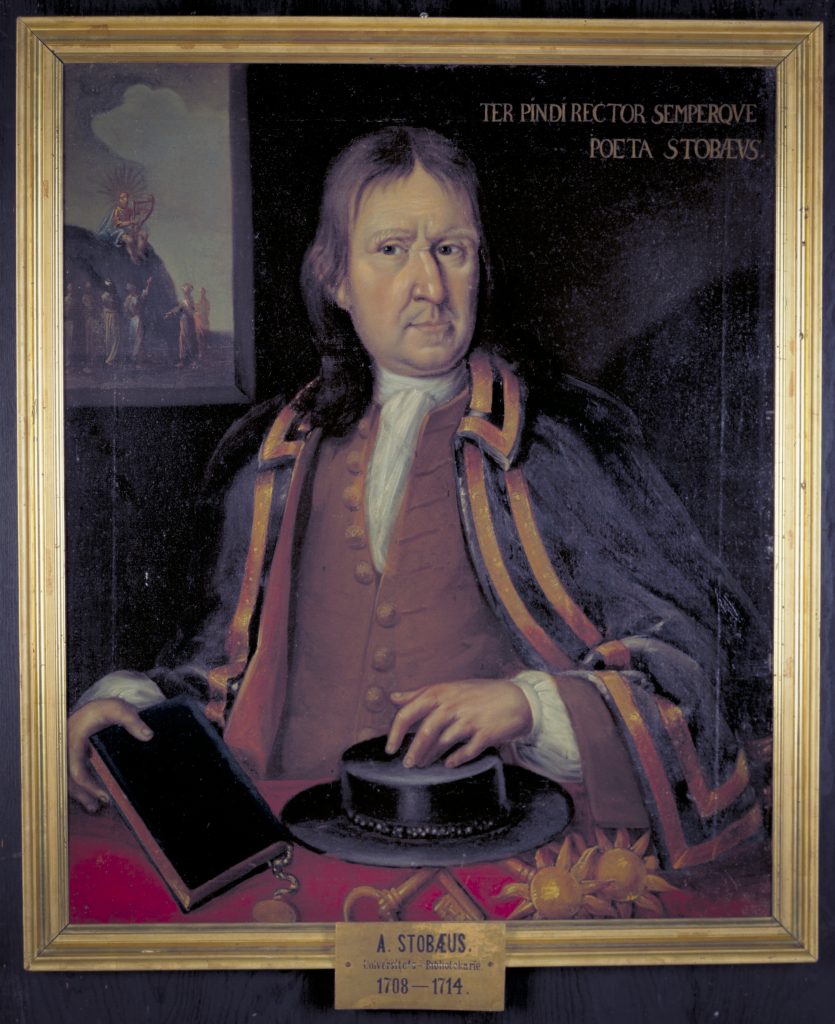

After that, the scepters remained in Lund and were – one assumes – used at the University’s ceremonies. Their status as one of the foremost insignia of the Vice-Chancellor’s dignity is illustrated by the fact that when Andreas Stobaeus had his portrait painted in (approximately) 1706, wearing his robe of office and holding the University’s statutes, the scepters lie alongside the University keys on the table before him as a clear symbol of his academic rank and authority. Since then, and up to our current time, the two seventeenth-century scepters – so the story goes – have accompanied the Vice-Chancellor at promotions, professorial installations and all manner of academic ceremonies and events.

Bingo!

But what about those two extra scepters in Kulturen’s silver vault? Despite the dramatic opening, it soon became clear to all involved that these could hardly be anything but copies. They were both much lighter and less sharp in detail than the University’s scepters – and they certainly didn’t weigh 1.5 kilos. The Chief of Protocol’s and Kulturen’s suspicions immediately fell on the now-closed University history exhibition that once existed on the museum’s premises. For that exhibition, copies of the scepters had been made; apparently, one and a half kilos of seventeenth-century silver were a bit too tempting for such a display. And despite a colleague’s confident assertion that the copies “were a pair of thin replicas in silvered plastic. I think they were thrown away when the exhibition closed. So they definitely weren’t the scepters you’ve just looked at”, I was able to prove him wrong by searching the archives of the Lund University Historical Society. Soon I found what I was looking for: an invoice from the Swedish National Heritage Board’s Antiquarian-Technical Department, dated 17 December 1998 – always these December dates! – for the tidy sum of 93,000 kronor for copying “two processional scepters from Lund University.” Bingo!

“But wait a minute!” I hear someone object, “93,000 kronor for ‘a pair of thin replicas in silvered plastic’ sounds like a lot.” And I am, albeit a public servant, inclined to agree. A closer study of the invoice, however, showed that my colleague was wrong; the copies were not plastic but made using so-called galvanic copying. In this process, often used to replicate coins for exhibition purposes, a mold is made for each side of the object, the mold is electroplated, and the two metal halves are joined. Something finer – and much more expensive – than a plastic copy, in other words!

The mystery of the two scepters at Kulturen was thus solved; they were galvanic copies made in 1998 for the Lund University Historical Society to be displayed in the University history exhibition. But the rabbit hole went deeper than that. Attached to the invoice were photocopies of two identical notes – one for each scepter – found inside the scepters when they were disassembled at the National Heritage Board. These were written by the Lund goldsmith Johan Petter Hasselgren in May 1868, and they added yet another twist to the entire scepter story.

Lavish celebrations

The sharp-eyed reader will note that 1868 is exactly 200 years after the University’s inauguration. This is no mere coincidence; Hasselgren’s notes were intimately connected to the University’s bicentennial celebration, held on 27–29 May that year. In the nineteenth century the spirit of the times demanded that a university anniversary be lavish. And Lund University did not intend to disappoint. Invitations went out to everyone of note in Sweden – and in many cases beyond. Professor Martin Weibull was commissioned to write the University’s history in two volumes. Jubilee medals were ordered. New uniforms for the academic guard and staff were tailored. Balls and banquets were planned. Jubilee cantatas, songs and poems were written and set to music. Military bands were contracted. The University keys were regilded. And over three days, in the presence of King Charles XV, Prince Oscar (the future King Oscar II), and representatives of Sweden’s elite, along with a large number of guests from the Nordic countries and Germany, both the jubilee ceremony and doctoral conferment ceremonies in all four faculties were conducted.

And amid all these preparations and celebrations, the University’s scepters were, of course, present. The symbols of divine and human wisdom were, if nothing else, destined to take part in the processions to and from the Cathedral. But if the fall from the bridge in 1668 hadn’t damaged them much, it seems the two centuries that followed left them somewhat worse for wear. It was therefore hardly surprising that the scepters were handed over to Hasselgren for some much-needed restoration, and in the letters found inside the scepters – beginning with “Honored Brother in Office” – Hasselgren explained that he (or rather his employee Carl Leonard Moberg) had “repaired” the stars atop the scepters. The existence of these letters was no secret – when they were discovered during the galvanic copying process, an article was even published in the University newspaper LUM about the find – but Hasselgren’s statement about the stars, combined with the note that they bore a silver hallmark from 1868, made me wonder what was actually documented about the 1868 repairs, and just how extensive they had been.

A Price Tag Worth a Small Fortune

The minutes of the Consistory (the equivalent of the University board) offered no clues. They spoke at length about the upcoming jubilee and various expenses related to it, but nothing was said about the scepters. At the same time, Hasselgren could hardly have done the work for free. Just as with the copies, it was ultimately invoices that provided the answer. In the University’s accounts were two invoices from Hasselgren. The first, from February 1868, charged the University 12 riksdaler for having “Repaired 1 Cursor-scepter” and “Gilded 2 keys” (the latter presumably referring to the aforementioned University keys). So far, so good – but a few months later, in May, came a scepter invoice that bodes ill for posterity. According to this, he had not only “Repaired and gilded the shafts” but also made “2 new stars” at a total cost of 126 riksdaler and 56 öre. It was not without a chill running down my spine that I read the words “new stars” and further noted that he deducted 51:41 for “97 ort [about 412 grams] of old silver.”

Hasselgren’s “repair” thus seems to have been a bit more heavy-handed than his letter suggested. Even if we cannot know with certainty what actions lie behind the terms “new stars” and “old silver,” it seems likely that Hasselgren and Moberg simply made entirely new stars and melted down the old ones – we might draw a parallel to the fact that only a decade later, a “renovation” of Lund Cathedral meant that both medieval towers were unceremoniously torn down and rebuilt with new material. So, it appears that the University’s scepters were not from the seventeenth century as we all had believed (at least not entirely) but, with the exception of the shafts, date back to the nineteenth century!

Such is life in the archival world. A 150-year-old invoice copy overturns everything we thought we knew about one of our University’s most visible symbols. A truly disappointing Christmas gift, albeit made of nineteenth-century silver. But at the same time, there is something beautiful in the fact that the truth, though somewhat uncomfortable, could come to light. Had it not been for the “divine and human wisdom” that ensured two invoices from 1868 were carefully copied and preserved for posterity, we would have continued living in a comfortable but false notion of how things really stood with the University’s silver scepters.

And does it really matter that our scepters are not one hundred percent seventeenth century? For the jubilee, C. V. A. Strandberg wrote a special jubilee cantata, which ends with these prophetic words (my translation):

Even through the centuries turning

Keep the lamplight lively burning

Shining through the blackened night.

Now – a grateful glance behind

Then – in promise anew us bind

To study, both in life and mind,

To progress, blazing roads to find –

To foundations lay, of truth and light!

Perhaps the union of the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries in the scepters is, in fact, a strength? A visible sign that Lund University has a long and varied past that leads us into a bright future? If nothing else, that is what I will try to think when I see the scepters’ stars “shine so bright” with their divine and human wisdom before the Vice-Chancellor at the University’s ceremonies. May they continue to inspire the University and its staff in the years to come.

And with that, I wish you all a Merry Christmas. If you like, feel free to put a star atop your tree.

Henrik Ullstad

Archivist at the University Archives

The author wishes to express his sincere gratitude towards Lukas Sjöström, Per Stobæus och Fredrik Tersmeden for valuable input, and to the Office of Special Events and Protocol, without whose initial question this article would never have been written.

P.S. These days, invoices at Lund University are destroyed after 17 years. O tempora, o mores!