Hi Charlotte Beskow! You are an alumna from the Faculty of Engineering, LTH, at Lund University with a MSc degree in Electrical Engineering. Since graduation you have worked in many different places around the world with missions connected to outer space. Can you tell us more about your career from Lund to the world of space technology? And tell us what inspired you to pursue a career in this industry?

Thank you for asking me to participate to this blog! My yearning for adventure and of doing something interesting with my time has led me on an interesting journey that I could never have dreamed of when I grew up.

My first job was at Ericsson Telecom, but starting salaries in Sweden were low and life in Stockholm was expensive. A colleague showed me an ad for Saab Space and this is how I discovered that Sweden had a space industry. I moved to Göteborg and thoroughly enjoyed myself for two years before changing to the European Space Agency (ESA) in the Netherlands. One driver for the move was the sheer scale of ESA’s activities. Space is a big domain and covers everything above roughly 110 km altitude. The European Space Agency, covers all aspects of space: scientific exploration missions within our Solar System, Earth Observation from Low Earth Orbit, mission control, launcher development and infrastructure, technology development, telecom, navigation, human spaceflight and much more. Since staring at ESA in 1988 my main activities were in two areas: the European contribution to the international Space Station and launchers.

Can you share an example of a project or initiative you led that you are particularly proud of during your time at the European Space Agency?

Space is about teamwork. Projects are decided on the ministerial level and the Agency then appoints a multinational technical team that leads/monitors the work done by Industry. The “interesting” work is therefore mainly done by industry while the ESA team manages the work, checks on progress, monitors cost and schedule and takes major technical decisions together with industry.

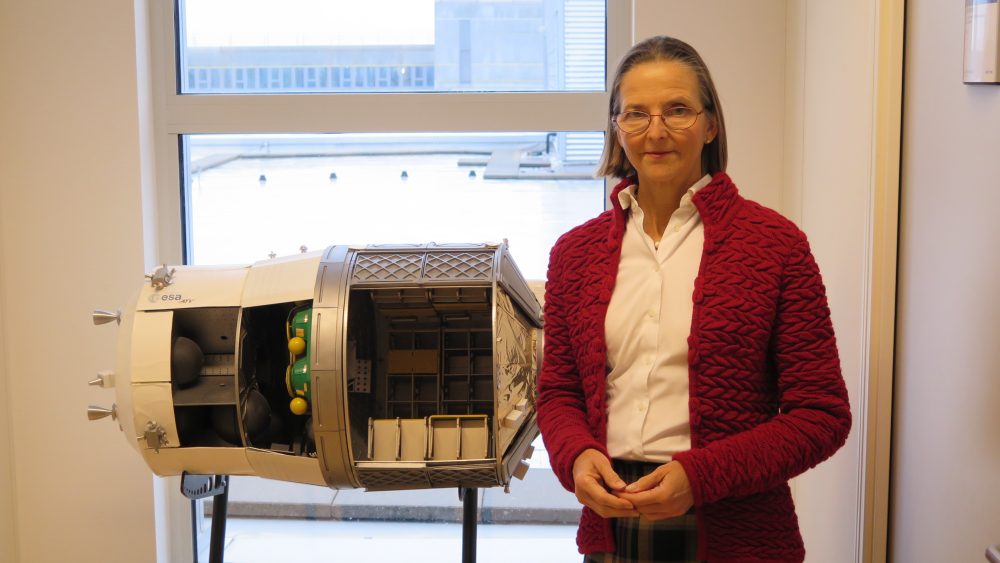

I had the fortune to work on a project where we were much more closely involved in the technical work. The European Automated Transfer Vehicle (ATV). It was technically and managerially a very complicated project. Developed by a French led consortium, the mission was to carry cargo to the International Space Station (ISS), located between 350 and 450 km above the Earth, doing one orbit every 90 minutes. The ATV was to be launched atop an Ariane 5 rocket from French Guiana, locate the ISS, approach the ISS in a controlled manner (orbiting at a speed of 7.6 m/s or 28,000 km / hr) and then dock to the Russian segment. The size of a London bus and weighing 20 ton at lift off it could carry up to seven types of cargo in a mix determined by the needs of the ISS at the time of launch preparation. The vehicle was in two parts. The lower, unpressurised part, mainly consisted of fuel reservoirs, engines, antennas and receivers and all the various electronic boxes/computers required to perform the mission. The upper part was pressurized and contained the cargo for the ISS plus the active half of the Russian docking and refueling system and the 19 associated black boxes. Once attached to the ISS the pressure between ISS and the ATV was equalized and the crew could then enter the forward part. ESA had two small teams working on this major project. One for the flight segment and one for the ground segment, i.e. the control center that was being developed to control the ATV while in orbit. In order to ensure that the project could fulfill its objectives.

I worked on the flight segment and was co-responsible for all the crew interfaces as well as the definition of the operations reference, i.e. how to operate the ATV in all known nominal and off nominal situations. I was also instrumental in setting up the engineering support team, i.e. the group of experts that were to be on hand at all times to deal with problems in flight. I worked in the ATV from 1999 until the end of the 5th successful mission in 2015.

Given the current geopolitical landscape and potential diplomatic crises, how do you see these factors influencing international collaboration in space research and exploration? Are there specific challenges or considerations that space organizations need to address to ensure the continuity and success of space projects in such environments?

Space is an international endeavour. ESA today has 22 member states and has a close collaboration with other space agencies : NASA (US), CSA (Canada), JAXA (Japan) and until recently RSA (Russia). Many of our satellites are joint missions, mainly with NASA and JAXA. Even during the cold war there was collaboration and discussions with the Russians and I hope that this can resume once the political landscape permits it. In the meantime, projects we had with the Russian Space Agency are either put on hold or modified to find alternative ways to complete the intended purpose. Incidentally this iterative response to problems that arise is part of our daily life since things seldom work out as initially planned. All space initiatives are long term efforts. Technical difficulties occur when you are trying to do something that has never been done before and it is important to maintain the political support when the going gets tough. The benefits of space projects are not always immediately visible, just like the benefits of fundamental research, so when money is tight it can be tempting for politicians to cut our budgets. We need to get better at explaining the long-term benefits in order to maintain public support for what we do.

In your opinion, what do you see as the most exciting developments or challenges in the future of space exploration?

Cybersecurity and space debris are two important areas that need to be addressed. Debris poses a risk to satellites. “Cleaning up” space sounds easy but is a daunting task, both dangerous and costly. It is important that spacecraft operators remove their spacecraft once they are nearing their end-of-life. A collision between a satellite and a piece of debris creates thousands of new debris that in turn pose risks in a never ending negative cycle.

Can you share some key experiences or projects from your time at LTH (Faculty of Engineering) that influenced your career path?

Thanks to the initiative of Inge Brinck, I had the opportunity to study one year at ENSEEIHT in Toulouse. The purpose was to learn fluent French, which I did. This is what has given me an edge in the space industry. Thanks to my command of languages, I was able to work at the launch base in French Guiana, which gave me the necessary operational experience to be a key part of the ATV team. The successful ATV project then allowed me to finish my career as Head of the ESA Office in French Guiana.

As someone deeply involved in space exploration, we have to know: if you could travel to any celestial body in our solar system (besides Earth), which one would it be, and why?

We humans are not designed to live anywhere but on Earth. Having said that, if I was offered a ride to the ISS, or even a 15 minute suborbital flight I would take it and never mind the consequences.