What does a self-proclaimed king of Corsica have in common with a young Ukrainian nobleman?

Well, both are said to have been students at Lund University during a time when the sources are far from watertight. Between 1693 and 1719, the University’s central matriculation register is missing – an historical gap that opens the door to both speculation and intriguing stories. Fredrik Tersmeden, Honorary Doctor of Philosophy and archivist at the University Archives, shares how the Ukrainian nobleman Georg Orlik – unlike the mythical Theodor von Neuhoff – actually left traces behind in Lund.

An alleged Lund student

If one wishes to assert that an historical figure studied at Lund University, without the risk of the claim being easily disproven, then it is wise to choose someone who was active during the period 1693–1719. This is because the University’s central register of enrolments for those years has long since been lost.

One person said to have studied at Lund during that time is the German adventurer Theodor von Neuhoff (1694–1756), best remembered by posterity for briefly making himself King of Corsica. According to various older sources, Neuhoff, filled with admiration for the warrior king Charles XII, sought him out during his time in Lund and, in the process, is said to have enrolled at the University (for some reason under the name “Norrman”). Modern research has established that von Neuhoff was indeed in Swedish service for a time, but there is general agreement that he never actually set foot in Sweden – let alone in Lund.

But what about another young foreigner, also linked to Charles XII, who is likewise said to have studied in Lund during these years: the Ukrainian nobleman Georg Orlik? Here, it seems, the evidence is somewhat firmer than in Neuhoff’s case.

Before we delve into the source situation, however, it’s worth first taking a moment to understand who this young man actually was.

Ukraine’s freedom fighters in Swedish exile

Georg Orlik (also known as Gregori Orlik, Grégoire d’Orlik or Hryhor Orlyk – we are speaking of someone who lived and worked in many countries, using different languages and even different alphabets) was born in 1702 in Baturyn, Ukraine. At the time, this town served as the country’s capital during the Cossack leader Ivan Mazepa’s attempt – supported by Charles XII – to liberate Ukraine from Russia. Georg’s father Filip (also written Philip or Pylyp) was one of Mazepa’s closest allies and, after the latter’s death in 1709, took over as hetman of the Zaporizhian Cossacks, albeit in exile. By then, Mazepa and Charles XII had already been defeated at the Battle of Poltava, and both father and son Orlik had fled with the Swedish king to the Ottoman Empire. In 1715, they followed him to Sweden.

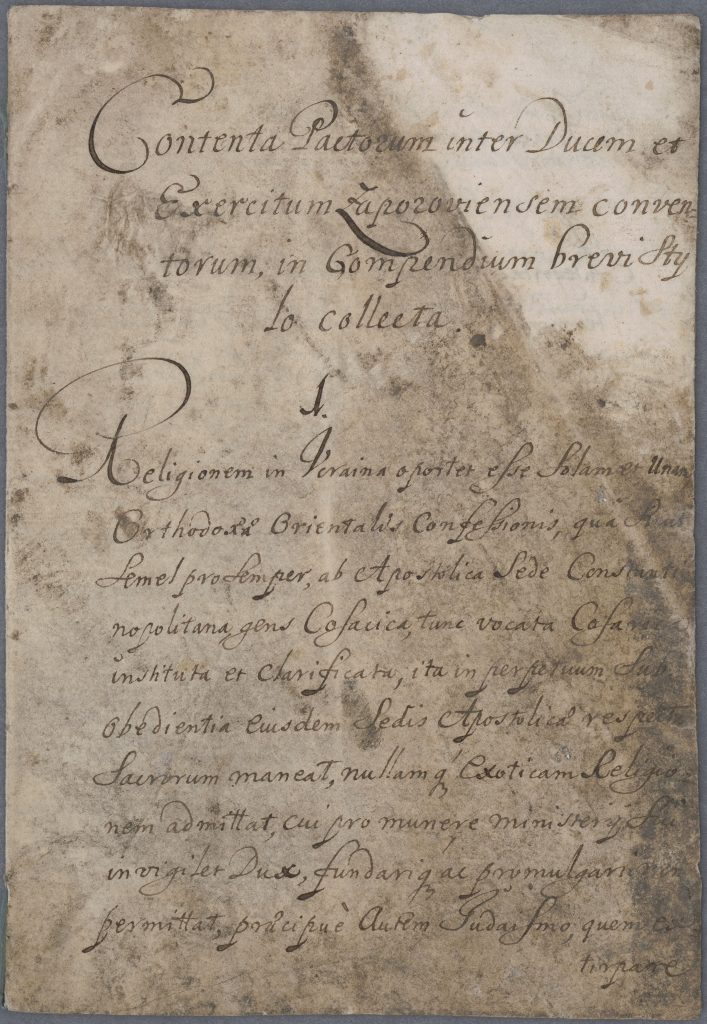

Unlike in Neuhoff’s case, the Orlik family’s stay in Sweden and Scania is well documented by both international and Swedish scholars. The family – consisting of father Filip, the eldest son Georg, mother Anastasia, two other sons and four daughters (a fifth daughter was born during their time in Sweden) – lived in Kristianstad until 1720. Filip Orlik would go on to campaign for Ukrainian independence from various parts of Europe until his death in 1742, never severing contact with the Swedish government or royal family, as a number of letters in the Swedish National Archives show. Not least, the Archives hold a unique and central document in Ukrainian history: a handwritten Latin version of Ukraine’s oldest constitution, drafted by Orlik in exile in Bender in 1710. This symbolically important document was exhibited in Kyiv during the country’s 30th anniversary as a sovereign state in 2021.

Absent from the registers – but not from the library?

So much for Orlik senior and the archival traces he left behind, but what about his son Georg and the claim that he studied in Lund? To begin with, it can be noted that Orlik does not appear in the printed editions of Lund University’s matriculation registers, published in instalments between 1926 and 1932 by Per Wilner, later director of the University Library. This might seem unsurprising since, as already mentioned, the original register from Orlik’s time no longer exists. However, Wilner managed to reconstruct much of this missing period using other sources in the University Archives (then kept at the library), including the register of the Faculty of Philosophy, the matriculation books of the student nations and occasional preserved attendance and fee records. Still, the result is far from complete. As a nobleman, Orlik would for example have been exempt from the requirement to join a nation, and might thus have escaped inclusion in many records.

Nor is Orlik mentioned in the list of historically notable alumni compiled by Martin Weibull and Elof Tegnér for the university’s 200th anniversary in 1868. In fact, very few (if any) overviews of Lund University’s history seem to have taken note of the claim that the son of an exiled foreign head of state once studied here.

An historian who, on the other hand, does mention this is Carl Grimberg, the well-known author of Svenska folkets underbara öden. In volume 5 of the original edition (published in 1916), he briefly notes “the Cossack hetman Filip Orlik and his son Grigorij, who for a time studied at Lund University.” However, Grimberg provides neither sources for, nor further details about this brief paragraph.

A 13-year-old in the military service

Luckily, there is a work that does provide a source. It is a biography of Georg Orlik, written by the Ukrainian-born historian and Slavist Élie Borschak, who lived in France. His biography of Georg was first published in Ukrainian in 1932 and later in English in 1956: Hryhor Orlyk – France’s Cossack General. According to Borschak, Georg (or Hryhor, as Borschak transcribes his name) entered Swedish military service at age 13 and took part in fighting in Stralsund, but:

A year later Hryhor left the military service and entered the University of Lund to study metaphysics under Professor Andrew Regelius. Hryhor thought very highly of his teacher who “captured the interest of his students with his profound thoughts, sincere heart and unshaken eonvictions.”

The final part of the quotation comes from a letter written by Georg Orlik to his father in 1731. That would appear to settle the matter, but unfortunately, a strict source critic would still find some issues. First, the book does not state which archive holds the letter, making verification difficult. However, assuming Borschak’s general scholarly reliability, we might choose to trust his account. Second, a self-reported statement by the alleged student many years later does not in itself constitute objective proof. But one might reasonably argue: why would Orlik lie to his father about something his father would almost certainly know? A third and more difficult issue is that there was no professor in Lund named Regelius at the time. However, there was a professor Andreas Rydelius, who taught metaphysics (today we would call it theoretical philosophy). Without being an expert in the Cyrillic alphabet, one may reasonably suspect that a transcription error occurred between writing systems.

Undeniable evidence

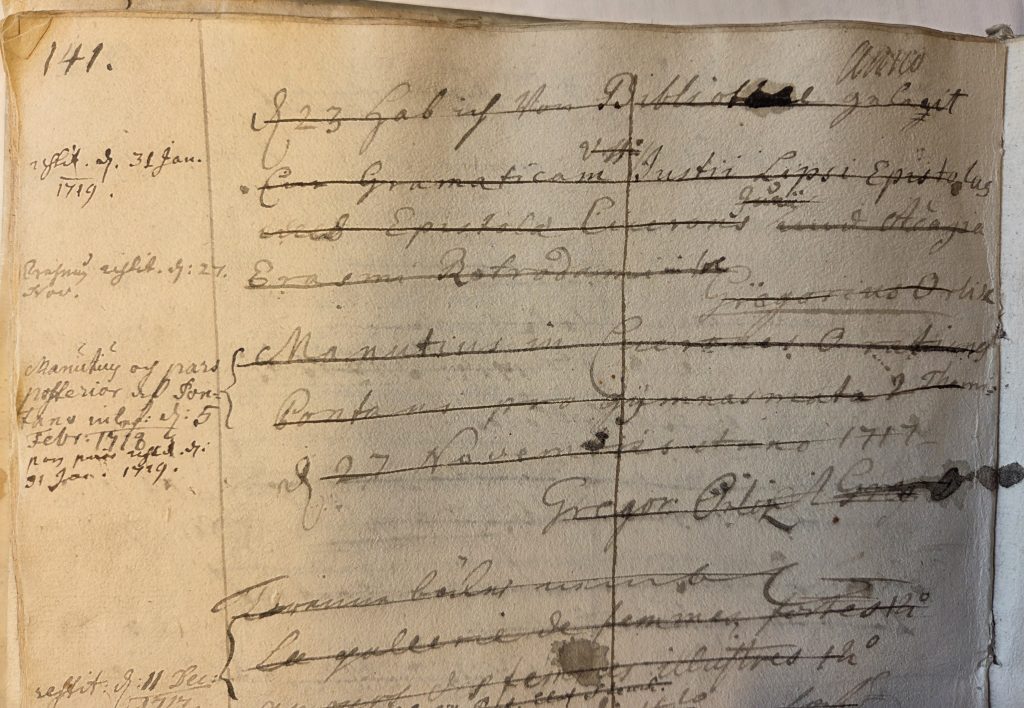

Should someone still not be satisfied with Orlik’s own statement about his studies in Lund, there is now fortunately undeniable evidence. Borschak reports that he received confirmation from Lund University Library that Georg Orlik personally signed out books on at least four occasions between November 1717 and May 1718, recorded in the library’s loan ledgers. (Borschak, unfortunately, does not specify from whom at the library he received this information or when. If it came from Per Wilner, then it would presumably have been after the matriculation volumes were published.)

So what did a 15-year-old foreign student of philosophy borrow in the early 1700s as “course reading”? Among the books were: a Latin grammar by the Belgian philologist Justus Lipsius, Paolo Manuzio’s annotated 1572 edition of Cicero’s speeches and several volumes of Jacobus Pontanus’ Progymnasmata sive dialogi – a widely used series of Latin textbooks in dialogue form. Altogether, a collection that reflects the classical learning ideals of the time and its instructional language: Latin.

Two of Orlik’s loans, however, appear more personal: one was a prayer book, the other likely a liturgical manual, both in Russian. Interestingly, although the books were in Latin and Russian, Orlik wrote his loan notes in German, while typically writing his first name in Latin: Gregorius.

According to the loan ledger, Orlik returned his final books on 31 January 1719. The following year, the Orlik family left Sweden, and Georg would spend the rest of his life based mainly in France. There, he became both a diplomat and military officer, and was involved in Louis XV’s secret intelligence service, working, it seems, to continue the cause of Ukrainian independence.

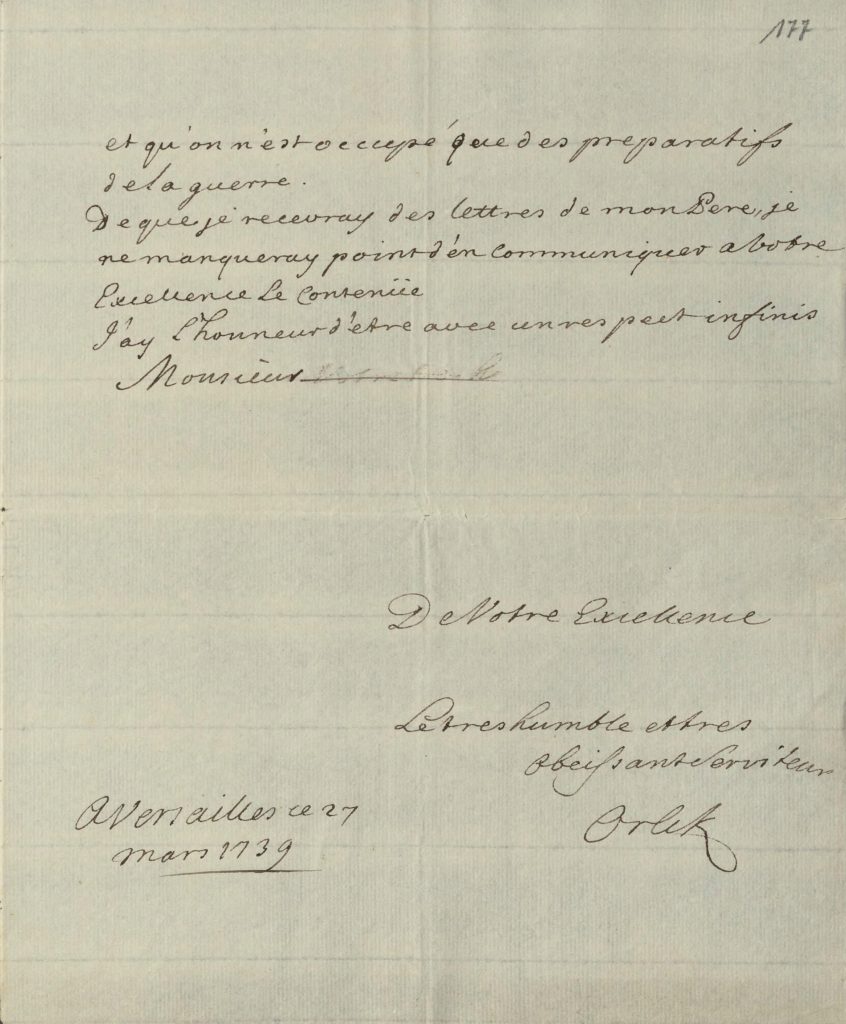

Orlik played a role in the peace negotiations in Belgrade following the Russo-Turkish War of 1735–39, and it is probably no coincidence that several letters survive from him to the Swedish Chancellor Carl Gyllenborg from 1739. This adds yet another Lund-related connection, since Gyllenborg was not only Chancellor (roughly Prime Minister) of Sweden at the time but also Chancellor of Lund University.

Orlik’s military career also included a more indirect Swedish link: the French regiment Royal Suédois, where many officers were Swedes. It was with this unit that Orlik, in 1747, received his commission as an officer. He fought in several battles of the Seven Years’ War, rising to the rank of lieutenant general and being granted the title of count. Perhaps more meaningful to him, though, was being made Foreign Commander of Sweden’s Order of the Sword by the newly crowned King Adolf Frederick in 1751. A replica of this honour was crafted in 2020 for a permanent museum exhibition in Orlik’s birthplace, Baturyn.

Georg Orlik did not, however, get to close the circle of his life in the same way. He fell in battle at Minden on the River Rhine in 1759, and was buried in a today unknown location nearby. Of his 57 years, he had spent 50 in exile, including one or two as a student in Lund – something we would never have known for certain had it not been for the University Library’s meticulous preservation of its old loan records.

Fredrik Tersmeden

Dr.h.c., Archivist at the University Archives

With warm thanks to librarian Per Stobaeus, who swiftly provided images of Orlik’s loan records from the University Library.