Fredrik Tersmeden, honorary doctor of philosophy and archivist at the University Archives, shares the story of Hans Wilhelm Lindstedt, who in 1774 became one of Lund University’s first students with a non-European background. With a Swedish father and a ‘black mother’ from Batavia (now Jakarta), his situation was unique for its time, as he was neither a slave nor a heathen, but the son of a Swedish father and sent to the University for studies like other young men from prominent families.

Please note: Language and phrases used in this text are part of the historical record.

In December 1774, newspaper readers in Sweden could read about an event that had taken place in Malmö:

Last Sunday saw the baptism of a Blackmoor here, whom a Swede named Lindstedt sent here from Batavia some time ago, and who will later be sent to Stockholm. On this occasion there were festivities and ceremonies, which many people from the surrounding area came here to see.

“Moor” or “Blackmoor” was a common term at the time that lacks a direct modern translation. It referred in a broad sense to people of colour, perhaps primarily to indigenous sub-Saharan Africans, but could also be used for, for instance, Arabs and the Berber peoples of North Africa. And as can be seen from the notice above, it could apparently also be applied to people from Asia; Batavia is the former name of Jakarta, the capital of what was then the colony of the Dutch East Indies.

We can be fairly sure that the “Blackmoor baptism in Malmö” was a special and exotic event for the congregation and other spectators present. However, it was not without contemporary counterparts; rather, “Moors” were most fashionable in 18th-century Europe, including Sweden. Especially the royal courts were happy to feature them; the most famous Swedish example is Gustaf Badin, a freed slave from the West Indies who was given to Queen Lovisa Ulrika in 1760 to be brought up together with the queen’s own children, including the future Gustaf III. Incidentally, the youngster who was baptized in Malmö – a 15-year-old named Johan Fredrik – is said to have been sent to the court in Stockholm soon after this event.

Even locally in Skåne (Scania) there are other examples from this time of “Moors” who were brought to Sweden and baptized. For instance, the rich and powerful baron Fredrik Ruuth, who owned several Scanian estates, in 1786 had a 15-year-old “Black Heathen” freed from slavery, taught Christianity and subsequently baptized by the local vicar in Skårby.

However, even though the baptism in Malmö in 1774 was not a completely unique event, the newspaper article about it ends with a short note that can definitely be said to be so:

The aforementioned Mr. Lindstedt also has a son, who was born in Batavia to a black mother and is now a student at the Academy in Lund.

Fencing and private lessons

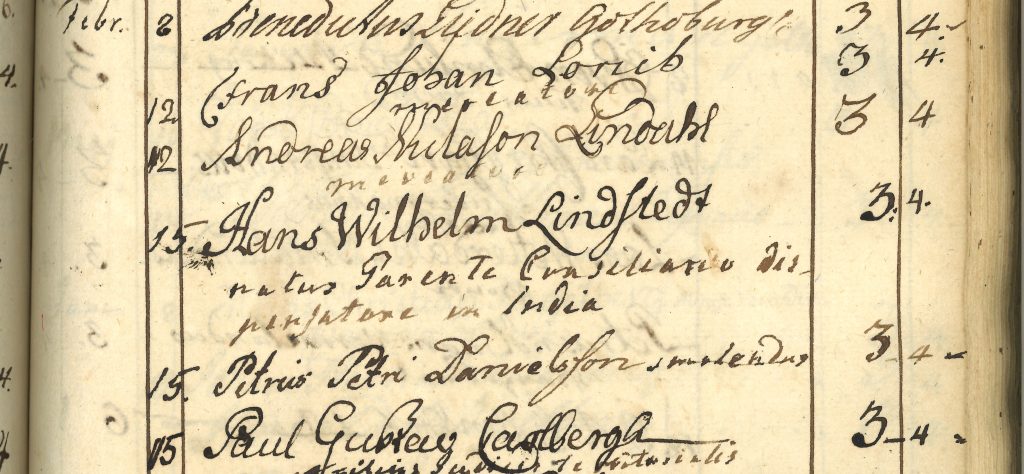

The fact that Lund University had a student of partly non-European descent already in the 18th century – more specifically, exactly 250 years ago this year – came as a surprise to me and my colleagues at the University Archives. This fascinating piece of news reached us by way of Johanna Berg who works at The National Museums of World Culture. She had come across this unusual student through the aforementioned 1774 newspaper article. Curious to know more, she contacted the Archive to ask if we had any more information about him, which we did: his enrollment data appears in the central student register from the that year. Here one could read that his full name was Hans Wilhelm Lindstedt, and that he was enrolled at the University on 15 February. There was also a note in Latin: “natus parente consiliario dispensatore in India”; that is, he is identified as the child of a parent who was an adviser in India.

After that, there was unfortunately not much else to be found in the University’s own official documents. Both the series of enrollment documents and the so-called term tables have large gaps in the 1770s, and Lindstedt could not be found there. Fortunately, however, the University Archives also keeps the documents from the Scanian student nation in which Lindstedt was also enrolled, and this source turned out to yield a significantly richer amount of information. Above all, the nation’s archive contained copies of the term tables that were missing from the University Archives, i.e. the detailed term-by-term accounts of all its members that the nations were required to send in twice a year.

To begin with, these tables gave us information about Lindstedt’s background beyond the single sentence in the enrollment register. Here we learned that during his first term in Lund, he was 14 years old and that his father was a merchant and “Member of the Council of Justice in Batavia”. Furthermore, it appears that he had not yet made a future career choice and that he “provided for through cash payment”. In the data for the autumn term of the same year (1774), he has turned 15 years old, and since the tables are dated, we can conclude that Lindstedt must therefore have been born between February and November, 1759. In this context, it may be noted that neither in the term tables nor in the enrollment register is anything said about Lindstedt’s mother or about the boy’s general ethnicity; hence, had it not been for the information in the press that he was the son of a “black mother” the natural assumption, based on the archive documents and the young man’s name, would incorrectly have been that he was the son of native Swedish parents who just happened to be living abroad at the time of his birth.

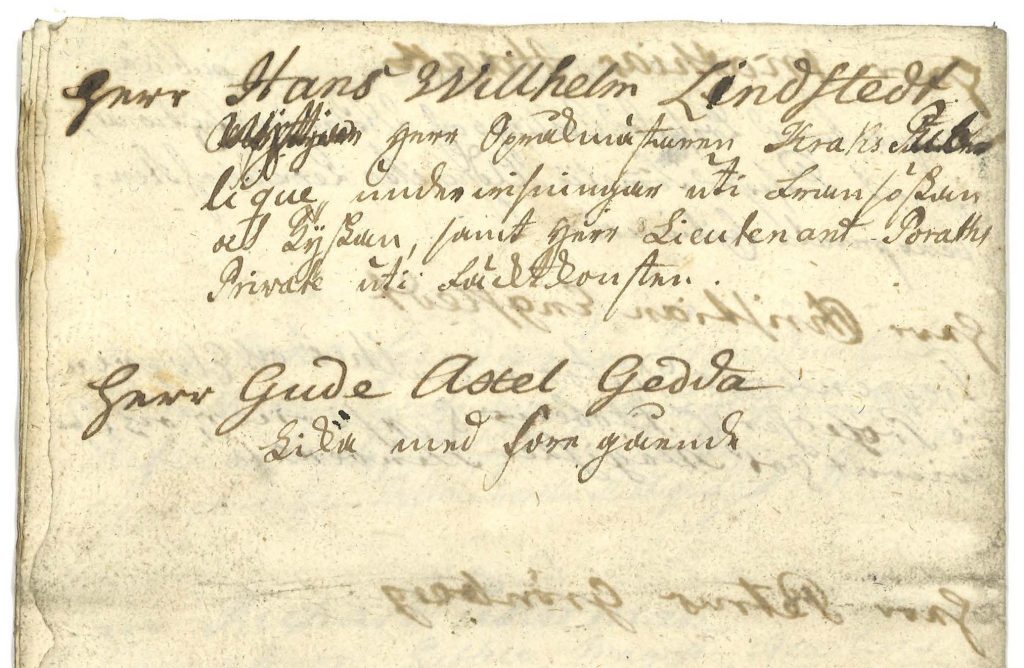

We can also follow Lindstedt’s studies term by term. During his first spring term, he claims to be attending language master Kraak’s public lectures in French and German, as well as taking private lessons with the University’s fencing master, Porath. In the autumn of the same year, he continues to follow Kraak’s and Porath’s teaching, but, above all, he enjoys the privilege of “private information”. In other words, Lindstedt had a private tutor. Often this person was a slightly older and more experienced student who replenished his coffers with these teaching assignments.

Lindstedt seems to have been absent from the University in 1775, since his name is missing from that year’s tables. In the spring of 1776, however, he is back, and now he attends professors Colling’s and Stobaeus’ lectures in Law and Latin respectively, and also takes private lessons in mathematics from a Master Cronholm. However, this is the last time Lindstedt’s name appears in a term table; after that he definitely disappears from the records of both the University and the student nation.

A fellow student became a “foster brother-in-law”

One thing you notice when you follow Lindstedt through the documents is that the same name keeps appearing right after his: that of Gude Axel Gedda, three years his junior. Not only are the two youngsters enrolled in the nation on the same day, subsequently appearing together in the term tables; they also attend exactly the same lectures and enjoy the same private tuition. It, therefore, seems reasonable to assume that the two boys were sent to University together and lodged together in the company of the same tutor. This assumption is supported by the fact that not infrequently the term-table notes for both Lindstedt and Gedda appear to be written by the same person – probably their tutor.

We also know that another clear connection between the two fellow students would appear later. Hans Wilhelm and Johan Fredrik, baptized in Malmö, were far from the only children that Lindstedt’s father sent to Sweden from his post in the East Indies: Johanna Berg has discovered three more, Apollo Doljalil, Pluto and Daphne, believed to have arrived in Sweden in 1777 in connection with Lindstedt Sr himself returning home, at least temporarily. Of these, the first two seem to have been of pure Asian descent, but Daphne – who in Sweden came to be known as Fredrica Dorothea – was of mixed birth like Hans Wilhelm. Her father was Fredrik Tott of Skabersjö, a Swedish nobleman, who was also in Dutch service in the East Indies, while the mother was said to be a Portuguese woman named Rita Brengman. However, Johanna Berg has doubted the latter information and leans towards the opinion that Fredrica Dorothea’s mother also belonged to the local population. The following contemporary account of her speaks for this:

In the house lived the son, captain Gedda, an educated man, but aloof and dignified, married to a Hindu woman, who called herself Tott and was said to be the daughter of a seafarer of that name, black and yellow in the face, slender and light as a feather.

As the reader may have already guessed, the “Captain Gedda” that Fredrica Dorothea married is identical to Hans Wilhelm Lindstetdt’s younger student friend. It can therefore be said that the two gentlemen over time became some kind of “foster brothers-in-law”.

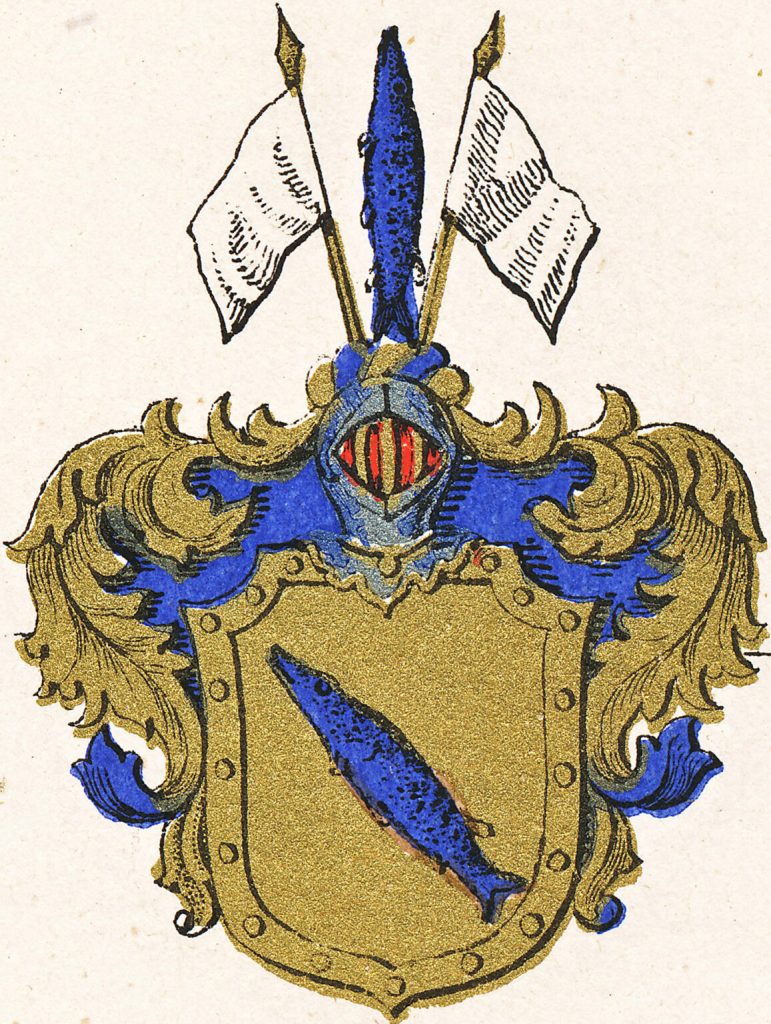

In time, Gedda not only got married, he was also ennobled in 1801. Lindstedt was not, looking at his and Gedda’s time in Lund, one sees an image of what was customary when the aristocracy and other upperclass parents sent their sons to University. One such distinctive feature is that, even by the standards of the time, they were so young when they were enrolled: 14 and 11 years respectively. Another is that, at least initially, they did not engage in any more advanced academic studies but focused on basic private tutoring and practice in social skills such as being able to fence and speak modern foreign languages. Last but not least, none of them graduated; something that was often considered unnecessary for the groups who stayed at the university more to get a general education than to invest in an academic profession. The statement that Hans Wilhelm and Gude Axel were provided for through “cash payment” also indicates that they, unlike many other students of the time, were financially independent. In short, they should have lived a pretty good life at University.

Back to the motherland

We are fairly well informed about how things later went with Gedda, thanks to the fact that he was ennobled and thus entered into the carefully kept rolls of the Swedish nobility. He became an officer in the navy (where he ended up as a major) and the owner of two estates in Småland, Öjhult and Grimarp, before dying in 1828. On the other hand, the information about Hans Wilhelm Lindstedt’s later life that both Johanna Berg and other earlier researchers have been able to find is very sparsely flavored. What is essentially known was actually summarized already in 1897 by the industrious personal historian Carl Sjöström in his printed register of the members of the Scanian nation:

[…] traveled to Amsterdam in 1781 to take up service in the Dutch army, but changed his mind and instead went to the English army in the East Indies, from where he wrote home around 1790 that he was a lieutenant there; has not been heard of since […]

The last traces of Lindstedt include that in 1807 he was wanted in the press on the grounds that he had an inheritance from a Mrs. Christina Elisabet Höppener to collect. However, there is no indication that this notice reached him, and we are thus forced to leave Hans Wilhelm here without final certainty about his further fate.

The first non-European

Hans Wilhelm Lindstedt was, as stated, far from the only person of colour in 18th-century Sweden; on the other hand, he was an unusual kind of non-white Swede of the time, both in that he was not a freed slave or “pagan” but had a Swedish father, and in that he was not kept as some kind of exotic curiosity at a court or in some noble family but was sent to University like any other young man from a better family at the time.

Nor was Lindstedt Lund University’s first wholly or partly foreign student. Already during the University’s first year of operation in the 1660s and 1670s, the student population had a distinctly international character. There were many Danish and German students, but also occasional youngsters from what is today Great Britain, the Netherlands and Austria. The unifying factor, however, was that they were all Europeans, and especially native Protestant Europeans. Lindstedt, on the other hand, was by all accounts the first Lund student with a partly non-European background and with at least one parent who was not white or perhaps even a Christian. And for thus having broadened the University’s international recruitment framework in this way, he should certainly be considered worthy of being lifted out of oblivion just in time for the 250th anniversary of his enrollment!

Fredrik Tersmeden

Ph D h c, archivist at the University archives

With sincere thanks to Johanna Berg, who provided much of the “extramural” information about Lindstedt and his family, and to my archivist colleague Henrik Ullstad, who helped with the archival research. Thanks also to my beloved wife Kiki Lindell Tersmeden, senior lecturer in English literature, for help with the translation of the text.