Throw up, spew, vomit, hurl, drop a pavement pizza – just a few of the countless synonyms for this “favourite” (well…or not) activity. The winter vomiting bug season has arrived!🤮

Carl-Johan Fraenkel, Consultant at the Infection Clinic at Skåne University Hospital and Region Skåne’s healthcare hygiene team, answers Lunadensaren’s questions about this recurring torment.

A confusing number of names for the virus

If you google ‘winter vomiting bug’, you will find a lot of articles that give three different names for the virus: calicivirus, norovirus and sapovirus. Can you straighten this out – is it the same virus? Why are there different names if it is the same disease?

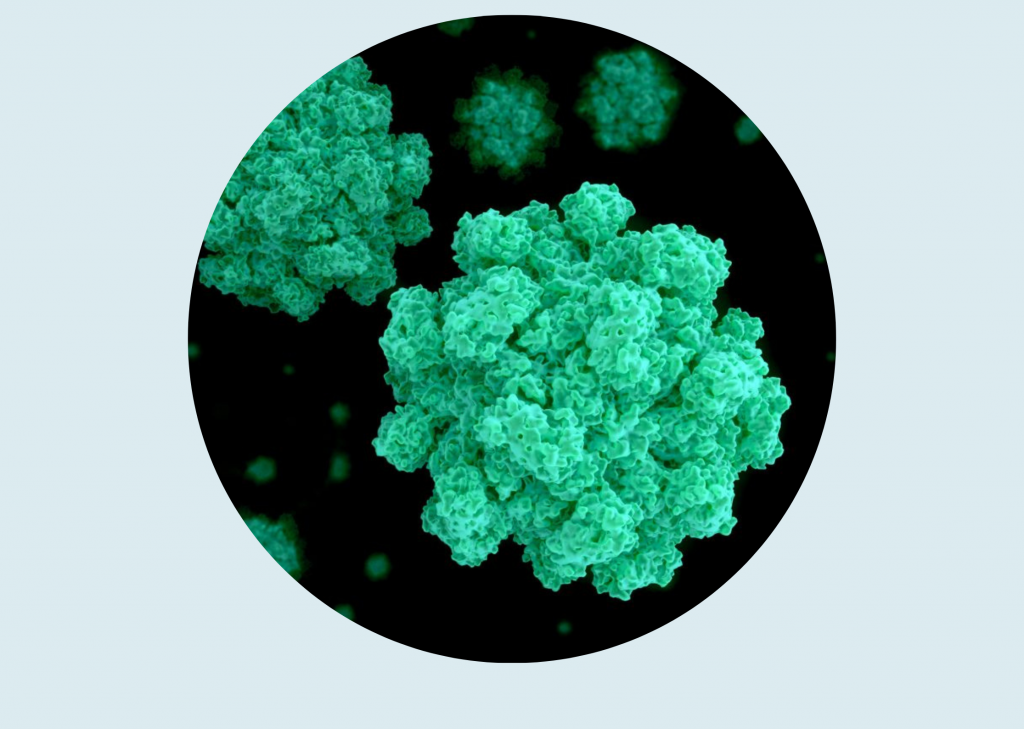

I think we should say ‘norovirus’ since that is what is used internationally and scientifically. But by way of explanation, you can look at the diagnosis. At first, these viruses were only seen via electron microscopes, and were given the wonderfully descriptive name, “small, round virus.” Later, when we learned about the genetics behind it, we realised that these viruses belong to the calicivirus group, and at first they were called calicivirus. Now we know that norovirus, sapovirus and others are part of the calicivirus group. Sapovirus results in similar symptoms to norovirus but is rarer. If you search for ‘calicivirus’, most of your results will concern feline calicivirus, which causes colds in cats. So use norovirus – that is the virus responsible for the winter vomiting bug.

Would we avoid getting sick if we moved south?

The winter vomiting bug arrives right on cue during the winter months, especially for young families – and as the name suggests, it is a winter germ – but does that mean that people do not have to worry about the winter vomiting bug at warmer latitudes?

The winter vomiting bug got its name in northern climes, since the virus seems to spread more effectively during the winter, but the virus is present around the world and is the most common cause of gastroenteritis (gastric flu) on the planet. It has been calculated that the virus affects 700 million people each year. There is a clear seasonal variation that has not been possible to fully explain. In Australia, the virus spreads mostly during their winter, but the seasonal variation is not as apparent in a tropical climate.

One for all, all for one?

It is said that someone vomiting with the bug will expel millions of virus particles, and that it only takes around ten particles to make you ill – is it even worth trying to protect yourself if someone in the family starts vomiting?

Good question – but I think it probably is. Infection is partly about the quantity of virus particles you take in, how it enters the body, but also how receptive you are. If you are partially immune, you can still become sick, but it takes a significantly higher dose of infection. So it is worth trying!

What is the best weapon?

What should you do to protect yourself?

Washing hands is the only thing that we know works. Cleaning is probably good, too. Someone who is ill should not prepare any food. The research we have done also indicates that the virus can spread in the air, in particles that are formed during vomiting, for example. It may be that face masks could help, but that is yet to be investigated.

A virus with wicked superpowers

We are told that hand sanitiser does not affect this virus – why is that? Apart from soap and water, what else should we be using?

Hand sanitiser works through the alcohol dissolving the fatty casing that surrounds all bacteria and certain viruses like an outer membrane – but the winter vomiting bug has no fat casing, so that is why it does not work. When cleaning, it is most important to simply scrub away as much virus as possible – manually. In hospitals, we use substances that have virus-killing properties. One such substance is chlorine. But you do not have to use such strong substances. Often a thorough ordinary clean is enough.

Trypanophobes can relax

Why is there no vaccine against this virus?

Great research efforts have been made to find a vaccine that works, but so far none have been found. There have been lots of difficulties along the way. Amongst other things, growing the virus in a laboratory has proved very difficult. The first successful attempt was in 2016, but the method involved is a complicated one. It has also been difficult to find an antibody that protects against infection and there are many different variants of the virus so a vaccine might need many different components in order to provide good protection. Hopefully, the progress made within vaccine development during the COVID-19 pandemic can help against the winter vomiting bug in the future.

Some parts of the population are not good at hand hygiene

How long is sensible to isolate after having an infection? Pre-schools usually say 48 hours while schools say 24 hours. What does the epidemiology say?

You are mostly contagious while you have symptoms, such as vomiting or diarrhoea. That is when there is a risk of a lot of virus particles being spread to your surroundings. The time is partly set to make sure that the stomach has recovered – you might feel fairly well but still have loose stools later. The fact that the times are different reflects the fact that pre-school children cannot take care of their hand hygiene as reliably as older children and adults. In addition, the virus remains in the gut for a long time in young children after the diarrhoea has passed, so it is sensible for pre-school children to be at home for a little longer.

Is this really true?

There are rumours that the winter vomiting bug didn’t exist in Sweden in the 1980s and 1990s. Is that true, or a myth?

It is a myth with a certain element of truth. The virus was first discovered in 1968 but has probably been around for a long time. Until the late 1990s, setting the correct diagnosis was very complicated – stool samples had to be sent to Stockholm for examination under electron microscope, and that was not something that was done as a matter of course. It is true, however, that the winter vomiting bug became much more commonplace in the early 2000s, not only because diagnosis improved but because of virological factors, too. A new kind of virus had developed that spread much more easily – norovirus type G2:4 Since then, new variants of G2:4 have emerged and spread at two or three-year intervals. When a new variant arrives in Sweden, we experience a winter with a lot of winter vomiting. It has now been several years since we were hit by a completely new variant though, which is why the last few years have been calmer.