Few alumni from Lund University are likely to have become news material in Hawaii. But exceptions exist. On November 27, 1933, readers of the Honolulu Star Bulletin were treated to a notice about a phenomenon in distant Sweden. Fredrik Tersmeden, honorary doctor and archivist at the University Archives, recounts the story of Kalmar’s first female student, Dagmar Karlberg – the mathematician who switched to become a translator and never tired of learning new things.

Few Lund University alumni can claim to have graced the columns of Hawaii’s newspapers. And yet, seek and ye shall find. On 27 November 1933, the Honolulu Star Bulletin featured a short piece about a phenomenon from a faraway place called Sweden: “Miss Dagmar Karlberg, 65 years old, living at Garvie, Sweden, claims to have taught herself Bulgarian, Rumanian, Chinese, Serbian and Turkish in just over two years.”

The news travelled further than Hawaii. The item came originally from the major news agency Associated Press (AP) and wandered its way through American newspapers from Brooklyn to Las Vegas in the autumn of 1933. The text was identical up to but not including the place identified as Miss Karlberg’s hometown, where local typesetters seem to have struggled with the exotic name. What in Honolulu had been “Garvie” became “Bavie” once it arrived in Gettysburg. In most cases, however, it was more correctly written as “Gavle”, or Gävle as we would know it, as indeed this was where Miss Karlberg lived at the time.

Learned in secret from her brother’s lessons

There was nothing upon her birth to suggest that Dagmar Karlberg would, in the autumn of her years, achieve world renown as a polyglot extraordinaire – nor, quite, that she would live to such a ripe age. Her father was a doctor at Kalmar’s main hospital to be sure, but not even this was a guarantee that a loved one would live long at that time. The year before Dagmar was born, both of her older sisters, aged five and two, were snatched from the family within mere weeks of each other. Presumably the arrival of a new daughter the following year, on 26 September 1866, was all the more eagerly awaited, and the feeling that she was a “replacement” for her deceased siblings was reflected in the fact that her three given names – Eva Dagmar Elisabeth – had all previously been borne by them.

In addition to the parents, Dagmar and the sisters who died in childhood, the family was rounded out by two sons: older brother Ivan (born 1865) and younger brother Gustaf (born 1869). Ivan started receiving lessons in the home when he turned five, which aroused his little sister’s curiosity. She was considered too young to participate, but as long as she promised to sit quietly, she was allowed to sit in and listen. The whole situation was later described in a newspaper article based on Dagmar’s own account:

She sat on a small stool in a corner with a doll in her lap. She was sure not to interrupt, but no one could stop her from listening intently. In this way, she absorbed everything that was possible to learn using her ears. At the end of the lesson, she would sneak up and look at the book being used, so that she could also read what was there with her own eyes. This was how she learned to read alongside her brother.

In those days, it was far from obvious that young women should be provided with any formal education beyond primary school level, and the state-run higher education system was exclusively geared towards men. But Dagmar Karlberg was doubly lucky. Firstly, she obviously had a family that supported her “desire for knowledge”, and secondly, Kalmar was a city with a number of private girls’ schools. The most ambitious and long-lived of these was the Nisbeth School, led by the enterprising Miss Georgina Nisbeth. One of her stated aims was “to ensure an education for young ladies equivalent in so far as it is possible to that which the boys avail themselves of in the public schools”. To achieve this, Miss Nisbeth recruited several teachers from the city’s boys’ schools to teach the older pupils at her school as well. Among which sat Dagmar Karlberg. She later wrote that “no experiences are so engraved in my mind as those seven years (1877-1884) which I spent at the Nisbeth Elementary School for Girls”.

Impudent enough to sit the matriculation exam

The fact that the industrious and well-read Dagmar was thriving at school did not equate to peace and happiness in the Kalmar doctor’s home, however. Her father suffered from a “premature collapse of health due to studies and work”. After periods of leave, he was forced to resign from the hospital in 1883, aged only 53, which explains later reports that Dagmar Karlberg came “from a poor family”. The situation was hardly improved by her father’s death two years later from an inflammation of the kidneys. Her older brother Ivan took his chance to emigrate to Australia, leaving his mother behind with his two youngest siblings Dagmar and Gustaf, both not yet of age. The latter had two more years until he could sit the matriculation exam. Before he could take it, however, his older sister Dagmar, with her Nisbethian education and a few more years of self-study behind her, was “impudent enough” (her own choice of words) to march up to the boys’ school in the spring of 1887 and declare that she wished to take the examination as an “independent student”. This had never happened before in Kalmar and threw the school management into a quandary.

The honourable headmaster did not know how to deal with me. He scratched his head and said:

“It is quite impossible for the young lady to sit among the men, they would be too distracted.” So, I was placed downstairs in the headmaster’s office, which was locked, and there I sat in splendid isolation and completed the written assignments. Well, then came the oral exam, and after that the moment when the happy graduands would, as was the custom, run out into the square and into the arms of all the mamas, papas, brothers and sweethearts to be embraced and cloaked with flowers. But I was not allowed to be part of it. It would have been “inappropriate”. Instead, I had to sneak out the back door – even though I had obtained laudatur [the highest grade].

Despite the discreet exit, it did not go unnoticed that Kalmar had received its first female matriculand. Kalmar Nation at Uppsala University drew attention to it by inviting her to a student party that summer; an invitation that Karlberg was forced to announce via the press that she had not received in time to accept. There was no immediate departure for a seat of higher learning – Uppsala or elsewhere – however. Instead, she spent the following year applying herself to a new subject, Latin, only to complement her examination in the same year as her younger brother Gustaf received his white cap. With the two remaining children thus ready to matriculate, their mother moved with them to Hjortgatan 5, Lund in July 1888. In September of the same year, both siblings enrolled at the University; Gustaf as one of more than a hundred male students that semester alone, Dagmar as Lund’s seventeenth ever female matriculand.

Keeping a low profile

Women were few and far between at the University when Dagmar Karlberg started. However, the autumn semester of 1888 saw a sharp relative increase in the number of female students, with no less than five young ladies enrolled within a few weeks. Several of these came to form a network with the older students, but judging from recollections of that time, Dagmar Karlberg does not seem to have been among them, and one can wonder why. Perhaps it had to do with the fact that Karlberg had come to Lund with her family and did not need to build a new community in the same way as the women who had travelled from far away? Or perhaps it was also that the family’s troubled financial situation meant that Dagmar had to spend a lot of time helping her mother in the household alongside her studies?

Karlberg’s progress was comparatively slow in the beginning, which suggests that the latter supposition was the real reason. While younger brother Gustaf graduated with a bachelor’s degree after just one and a half years, it took Dagmar four years to do the same. Their roles soon reversed, however. Gustaf submitted a licentiate thesis in the spring of 1895, but as he did not complete the associated examinations he did not receive his degree until many years later (1903). By then, his older sister Dagmar had already completed her licentiate degree in the autumn of 1895.

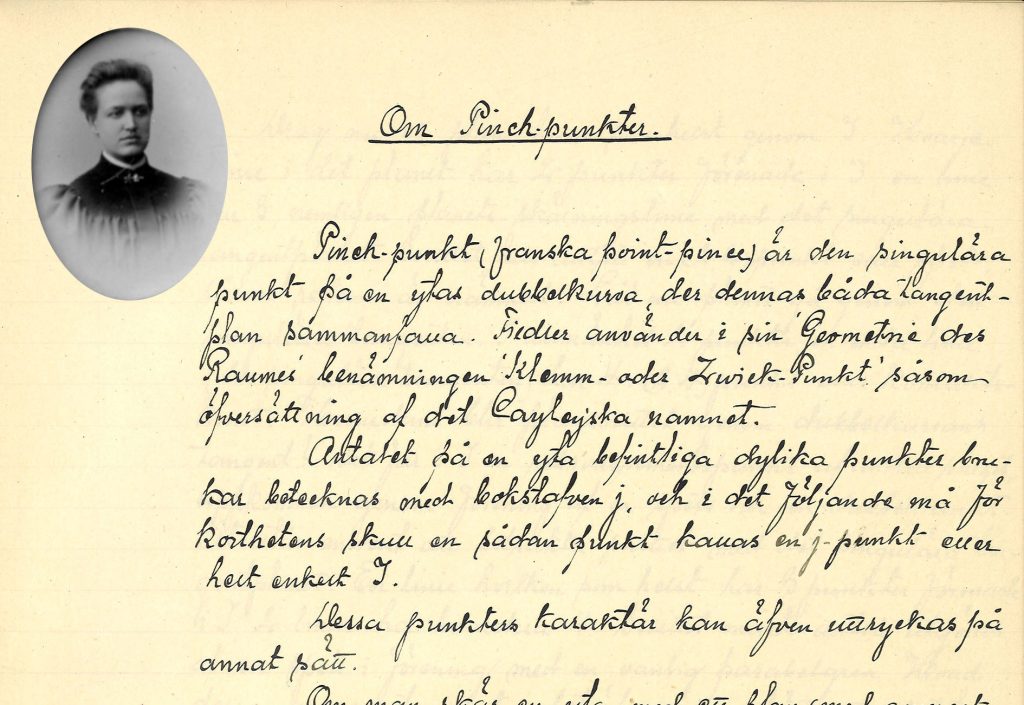

It is striking that there is no hint in the documents relating to the Karlberg siblings in the University archives that Dagmar would go on to become known as a polyglot extraordinaire. Quite the contrary: Gustaf was the student of the humanities at the Faculty of Philosophy, where he presented a thesis that was a translation of an ancient Egyptian temple inscription. Dagmar, in contrast, studied the natural sciences and wrote her thesis in mathematics and mechanics on pinch points! As a recent graduate, she also advertised in the local papers that she was offering private lessons in maths.

Soon Dagmar Karlberg would take up teaching in a more organised way than the private lessons: she became a schoolteacher. This was not surprising; among the earliest female students at Lund, the most common careers upon graduating by far were either as doctors or teachers, especially in girls’ schools. And it was these schools where Karlberg worked: in Norrköping, Halmstad and finally Skövde. All her positions were short term, however, and Karlberg soon realised that this was not what she wanted out of life. One reason was financial: “it was poorly paid, only 800-900 crowns a year, and I had student debts to pay off”. But there was also a new focus to her personal interests. In contrast to the natural sciences that she had hitherto mainly studied and taught, a love of languages “burst into flame”: “I had an intense desire to learn as many languages as possible,” she later said. And hence her first programme of continuing education: in the summer of 1898 she attended a course at Karl O Lindbergs Handelsinstitut in Gothenburg. This, combined with her own language studies, prepared her for what was to become her new commission: as a “foreign correspondent” handling international correspondence for various clients.

Translated “propaganda”

Karlberg’s first job in this new field was “at a large industrial company” in Gothenburg, which went, in her words, “bust”. She would go on to have better luck with similar positions at first the Skultuna brassworks, later the Husqvarna weapons factory and finally the shipowner Erik Brodin’s shipping company in Gävle. In between, she also managed stretches working in diplomatic circles, namely at the US consulate in Bergen and the Greek consulate in Helsinki. In parallel, she also advertised her services as a freelance translator.

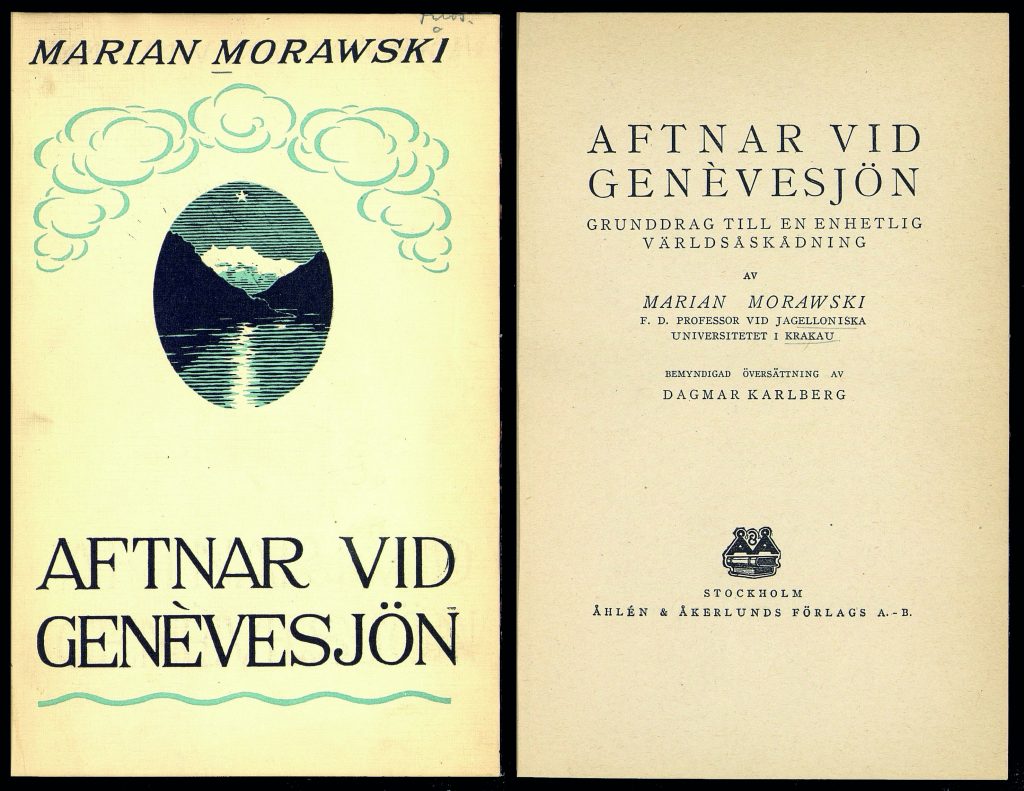

Eventually Dagmar Karlberg decided to go it alone: from around 1917 she was no longer employed by anyone but ran her own translation agency and gave language lessons in Gävle. It is likely that most of the assignments she received continued to be of the more formal and mercantile nature that she had undertaken when working for companies and consulates, and there is no indication that she had ambitions to pursue a more literary translation career – with one notable exception. In the spring of 1920, Åhlén & Åkerlund published the book Aftnar vid Genèvesjön [Evenings on Lake Geneva] in an “authorised translation by Dagmar Karlberg”. The author was philosopher and professor Marian Morawski (1845-1901), and the book had originally been published in Polish in 1893. Whether the translation was commissioned by the Swedish publisher or initiated by Karlberg herself is unclear. However, the preface she wrote for the book indicates the latter:

The book is not one of those that are read once and then forgotten. Permeated with the richest thoughts on the deepest questions of life, it grips its reader and takes him captive. [- – – -] Again and again, one turns the pages, only to find something new, something previously unnoticed, and when finally one puts the book aside, it is with the feeling of having found a real friend in it.

The book consists of a number of conversations among a group of international guests at a small hotel in the town of Ouchy, including two Poles (one of whom, a Catholic priest, is the book’s narrator), a Russian, a playwright from the south of France, a Swiss Protestant priest, a German legal philosopher and a female British novelist. Over the course of a series of chapters, they drift between various topics related to religion, science, knowledge and contrasting worldviews. A clear picture of the outcome of these discussions can be obtained by reading reviews of the book published in several Swedish newspapers at the time. These are characterised, it should be noted, by a rather critical tone, albeit not in relation to Karlberg’s translation but rather the message of the book. In what was still then a staunchly state-church Protestant Sweden, the book proved provocative because of its clear thesis that the real truth was to be found in Catholic doctrine – “straight to the Pope”, as one reviewer put it – while another described the book as a pure “Catholic propaganda” and a third said that the author served his thesis “on plates that were quite obviously fired in the factory kilns of Ignatius Loyola”. The latter referred to the founder of the Jesuit order, and the accusation was not without merit: Morawski had not only been a university lecturer but also an active Jesuit.

“A language should offer new perspectives”

It is not clear whether Dagmar Karlberg’s translation of Morawski was made directly from Polish or via another language. We do know, however, that she would eventually master a number of Slavic languages, and in general, it seems to have been during these years as a freelance translator that she increasingly began to engage in the self-study of various additional languages that would eventually make her, if not world famous, at least temporarily applauded as far away as Hawaii. This programme of learning gained real momentum, however, only after Karlberg decided to retire in the early 1930s. In the late summer of 1933, several Swedish newspapers reported that “an old lady” in Gävle had learnt five more languages – Bulgarian, Romanian, Chinese, Serbian and Turkish – in the two years or so following her 65th birthday, “merely for fun and out of curiosity”.

Articles on the linguistic virtuoso Karlberg continued to appear far and wide in the following decade. “Russian, Spanish, Romanian and Turkish” were her favourite languages it was claimed (later supplemented by “the soft Malay”) while Chinese was “interesting but impractical”. However, the only languages she found directly difficult were “Basque, Arabic and Hebrew” with Basque being the most difficult “because it is unlike any other language”. Bulgarian, on the other hand, was “child’s play” to learn in just ten days (!) due to her previous knowledge of Russian. Estonian – her 25th language – was something she “mollified […] her convalescence with” after breaking her femur at the age of 69.

Karlberg also said that she preferred to learn languages that were as different as possible from those she already knew – and especially her mother tongue: “a language should offer new perspectives and teach you something about ways of thinking that are foreign to a Swede,” she explained.

How proficient was Dagmar Karlberg in all these languages? Here, as in most of what we know about her study of languages, we must rely on her own testimony: “I do not know all of these languages in the sense of mastering them, of course. In that way I have mastered only my mother tongue. I am, however, able to make use of them, speak and write them quite well.” Being able to write was a key to Karlberg’s method of improving in these new languages. In addition to acquiring textbooks and other literature in and about them, she made sure to find people with whom to enter into a correspondence, wherever possible, such as “a Spanish priest, a professor in Vienna and a Dutchman” or even “a genuine Turk”.

It is an alluring thought that in the most scattered corners of the world, there may still be piles of letters sent by an elderly Lund alumna in Gävle. The story of Karlberg’s lifelong pursuit of knowledge becomes even more fascinating – and impressive – when you realise that she had had problems with her sight since childhood. By 1937 she related that she had lost all sight in one eye and had only about 10 per cent left in the other, but “thank God” she could still read “in bright light” and by holding a black ruler beneath each line as she went. Given these circumstances, it is not difficult to believe Karlberg when she said in another interview that “the desire for knowledge has been a mainspring throughout my life.”

At the age of 73, however, her studies were inexorably cut short. Karlberg had recently taken on her 28th language, Finnish, when her doctor expressly forbade her from continuing to read. Hungarian, which she intended to take on as language number 29, was to be left unexplored.

Cared for by the sisters

The photograph of Dagmar Karlberg in her old age at the beginning of this article comes from the County Museum of Gävleborg. The museum’s database states that it was taken on 20 October 1941 at Brynäsgatan 16 in Gävle. This was an address belonging to the Sisters of Saint Elizabeth, a Catholic order of nuns active in Gävle since 1892 who specialised in the care of the sick and elderly. Between 1933 and 1973, they ran a nursing home at that address where they “cared for many residents of Gävle”, some of whom also “ended their days at the home”. The register of deaths for Staffan parish in Kalmar shows that Dagmar was one of them: she ended her days with the sisters on 12 July 1945.

Given the small number of Catholics in Sweden at the time it was hardly a requirement to share the sisters’ faith in order to benefit from their care, but in the case of Karlberg in particular, one wonders whether the enthusiastic translator of Aftnar vid Genèvesjön might not have been particularly at home in a Catholic milieu where mass was celebrated three days a week. Regardless, she generally seems to have been a lady who found her place in life. Or as she put it in an interview at the age of 70:

It is so much fun to be alive, despite being old […]. Life has so many interesting things to offer. With interests and a good temperament, you will find happiness.

Fredrik Tersmeden

Ph.D.h.c, Archivist at Record Management and Archives