Fredrik Tersmeden, PhD h c, Archivist at the University Archives, opens the unpublished memoirs of Bengt J:son Bergqvist (1860–1936) to offer a personal look at Lund in the late 1800s.

The last day of April and the first of May is a time of year when many Lund alumni return to their former university town. Elder members of the Student Singers gather once again for the concert on the university building’s steps, former full-time officials of the student union, the Academic Society (AF) and the newspaper Lundagård reunite within the Order of the Magnolia, and ex-students in general come back to watch spex, listen to the aforementioned choir or simply enjoy the arrival of spring in the city – to quote Strindberg – “which one believes one can flee, but to which one always returns”.

One Lund alumnus, once very well-known, who gladly and regularly returned to the city was Bengt J:son Bergqvist (1860–1936). Between 1918 and 1928, he was the first Director General of the National Board of Education (Skolöverstyrelsen), and in 1920–1921 he also served in two Swedish governments as Minister for Ecclesiastical Affairs – that is, Minister of Church and Education. Before this distinguished career in the capital, however, he had spent many years in Lund: here he had been both a pupil and later a teacher at the Cathedral School (Katedralskolan); here he had lectured at the city’s teacher training college, and here he had pursued university studies at every level, from freshman to Doctor of Philosophy.

One reason Bergqvist made regular return visits to Lund was his old student class from the Cathedral School. The surviving members of the class faithfully reunited every five years. As late as 1934, when the group celebrated the 55th anniversary of their school-leaving exam, 18 of the original 40 classmates remained. Around the same time, Bergqvist was also working on his memoirs. Unfortunately, they were never completed or published, but a relatively complete typewritten manuscript covering the period up to 1904 has fortunately been preserved at Lund University Library. Thanks to this, we are able to revisit the academic Lund as Bergqvist recalled encountering it as a newly minted 19-year-old student in 1879.

Image source: Lund University Library.

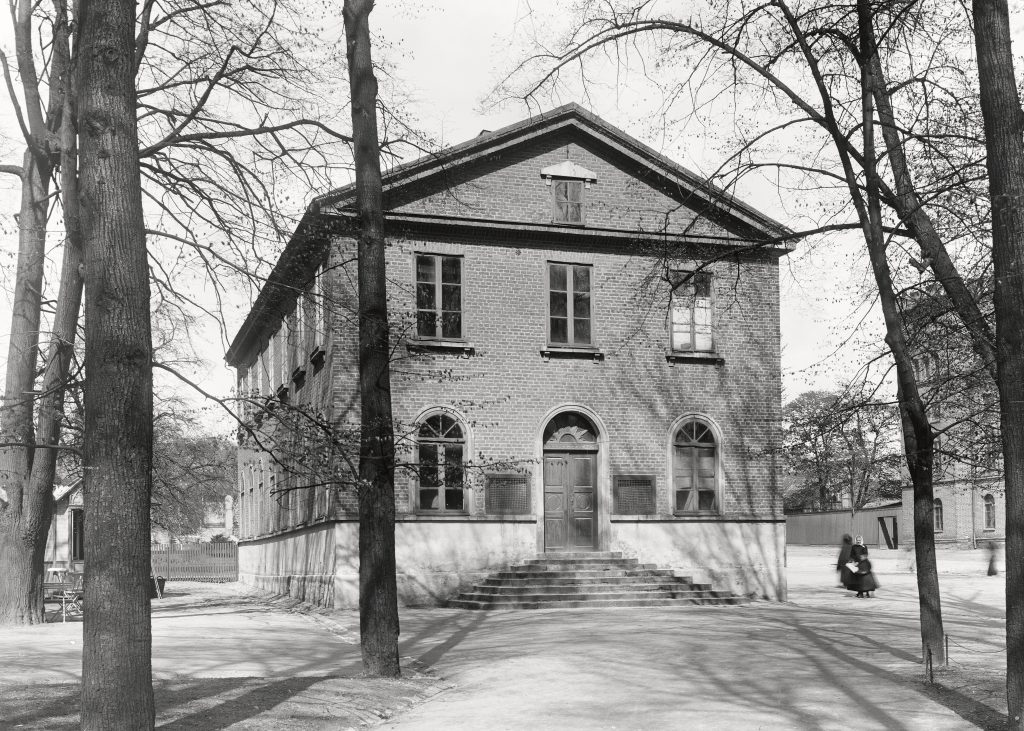

Bergqvist noted that at the time, there were four dominant “physical centres around which student life revolved”. The first of these was one which no living Lund alumnus of today has experienced – the University’s former main building. Bergqvist describes it as follows:

[…] an old building in fine and pure Renaissance style. Seen from the south, it was situated to the right of the former bishop’s palace in Lundagård [this refers to “Kungshuset”, once the home of bishop Peder Winstrup]. A later age, banal and lacking in reverence, has levelled that house to the ground, and today not even a trace remains to indicate where it once stood. It was commonly known as ‘Kuggis’, a derogatory nickname that eventually became a term of endearment. A tall, wide stone staircase led up to the building; its worn steps bore witness to the many feet that had climbed and descended them. Many a young man had climbed those steps with a trembling heart to undergo tests and examinations. Many had, after passing their trials, flown out of that house with hearts full of joy, headed towards uncertain but delightfully shimmering futures; others, however, had departed that building with heavy steps, dejected and downhearted, for it had become a ‘Kuggis’ – a place of failure – for them.

Bergqvist’s near-poetic description of “Kuggis” may come as a surprise to those familiar with other accounts of the building, where it is more often depicted as a shoddy structure with damp foundations and walls, draughty, unheated lecture halls, and overcrowded administrative offices – where even rector magnificus himself was housed in “a shabby archive room.” At that time, the building was also nearing the end of its use. Construction of the current university building had been underway for two years and it was due to be inaugurated in 1882. Bergqvist, however, expresses clear ambivalence towards this new, temple-like white structure – today one of the University’s most popular promotional images – referring to it as an example of the “ostentatious splendour so fashionable at the time.”

Image source: Lund University Library.

Opposite this new construction stood the second major hub of student life in 1879:

[…] the large building of the Academic Society (AF) on the north side of Tegnérsplatsen. On the ground floor were the newspaper room Athenæum, meeting rooms of various kinds, and finally a restaurant. Upstairs was the large ceremonial hall. It was surrounded by a balcony on whose outer edge the names of notable Swedes were inscribed. This hall was used for student union meetings and grand festivities. It was also rented out for all manner of more or less unrelated purposes. Thus, travelling theatre companies would hire it, and it served as the only theatre venue the city of Lund had to offer.

Bergqvist’s placement of the Academic Society “on the north side of Tegnérsplatsen” may seem peculiar today, when the front and main entrance of the AF building clearly face Sandgatan. However, prior to the 1911 extension, only the southern, square-shaped section of the current building existed, and its entrance did indeed face Tegnérsplatsen. Another difference from today lies in Bergqvist’s remark that the stage in AF’s grand hall was primarily used by “travelling theatre companies.” This reminds us that the tradition of spex – comic student theatre performed mainly by students themselves – had yet to flourish fully in the 1870s.

The two remaining centres described by Bergqvist differ from the former in being located outdoors. One of them still exists today: “the glorious old Lundagård, beneath whose great tree canopies the student singers, generation after generation, have expressed the emotions that stirred the youth educated at the seat of Alma Mater Carolina.” The other place has not entirely vanished but has been significantly transformed – the area we now know as University Quadrangle (Universitetsplatsen). To Bergqvist’s generation, it was still:

[…] the old Botanical Garden, located between Kuggis and the building that now houses the University’s gymnasium and music halls [i.e. Palæstra]. Towards Sandgatan, the garden was enclosed by a sturdy stone wall, a remnant of the wall that once surrounded all of Lundagård. There were numerous old, remarkable exotic trees and bushes, and most importantly, it contained a vast boxwood hedge, behind which many punsch tables were placed – from which student chatter and song rose skywards on glorious spring and summer evenings.

The mention of “the many punsch tables” leads Bergqvist into a broader reflection on student drinking habits of the time:

Back then, punsch was the students’ drink of choice. The variety of beverages with which today’s students quench their thirst was largely unknown to us. But it is almost unbelievable in what quantities this favourite drink, punsch, was consumed. There was no state monopoly on alcohol; individuals were free to handle spirits as they pleased. Punsch was even produced in some factories and private homes, with the quality of such home brews varying greatly. At larger student festivities, punsch was regularly served alongside specially prepared bowls. It was the golden drink of the day.

Up to this point, Bergqvist’s account may give the impression that student life was little more than a series of songs, parties, and drink. The memoirist, however, was well aware that there was a less glamorous side to life at the university in those days. Coming from a household where the father – despite being a vicar – suffered financial difficulties and had many children, and with government student loans still more than eighty years away, the economic realities for the Bergqvist family were acutely felt. Supporting more than one son at university was not initially possible, so Bengt’s younger brother – who had graduated at the same time – had to return home to act as tutor for their younger siblings. Bengt himself was only able to continue his studies by “helping schoolboys with their homework, thereby earning what I needed for my upkeep.”

This “upkeep” naturally included accommodation, and Bergqvist rented, together with a friend, “a small and humble double room located across a courtyard in a house on Råbygatan.” The term’s rent was 60 kronor – equivalent to about 4,400 SEK today. The landlady also offered “a cup of coffee and a bun in the morning for 10 öre.”

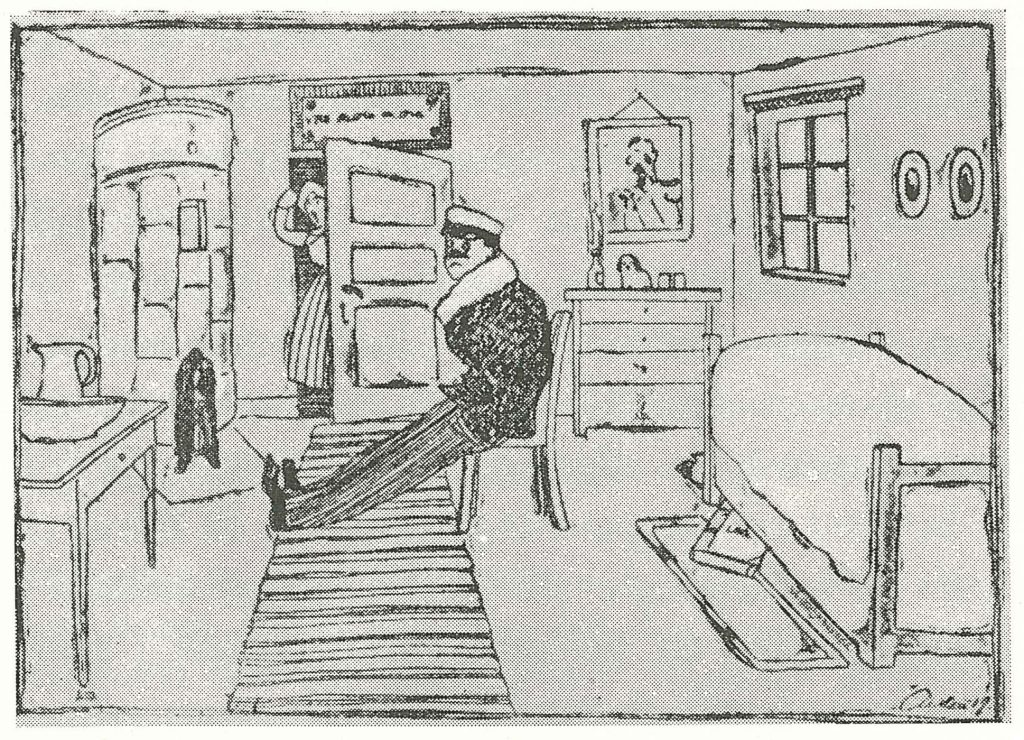

Bergqvist provides no detailed description of his own lodgings, but he does offer a general impression of what student rooms were like at the time:

Most of these rooms did not meet the hygienic standards of a modern age. Quite the opposite. Generation after generation of students – strong and weak – had lived in them, and cleanliness had often been poorly maintained. The rooms were usually rented furnished, with simple, shabby, and often worn-out furniture. A bed, a table, a couple of chairs, and possibly a sofa made up the standard set. In many places, one or more holes could be seen in the curtains – presumably from being set alight – a reminder of the fire hazard these rooms posed. Indeed, it is remarkable that in a city where so many student rooms existed at a time when lighting was provided by old, poor-quality paraffin lamps, and where punsch made students’ hands and legs unsteady, there were not more fires than there were.

Thus, the Lund student of the 1870s may often have been poor and lived modestly; yet, to paraphrase an old saying, it seems that money for punsch somehow always managed to float to the top!

Fredrik Tersmeden

Ph D h c, Archivist at the University Archives